On September 1, 2009, I embarked on a humbling journey of self-exploration to the heart of Africa. For a month, I immersed myself in the culture of the Maasai tribe while adopting and learning from their customs and culture in the rural village of Kajiado, Kenya. This 6-part series chronicles the experiences and observations while travelling.

Was it the limitless wonder in the enthralled eyes of the children? Maybe it was the picturesque backdrop of the rolling Ngong Hills. Or, perhaps it was the distinctive taste of nyama choma (roasted meat) as the succulent juices tickled my taste buds. Whatever factor came into play over the course of the month that I spent in rural Kenya, the culmination of them all resulted in an unforgettable expedition that would change my life indefinitely.

As I made my way from the urban center of Nairobi to the barren, pastoral town of Kaijado in the heart of Maasailand in a two-hour matatu (large van carrying 10-12 passengers) ride, I could not prepare for what I would encounter next. It was the vast wildlife that first caught my focus with herds of zebras, ostrich, and gazelles just beyond the window. With the Ngong Hills faded in the distance it was a striking setting to complement our Maasai arrival.

Upon arrival, I was greeted by Mike, the paternal head of the host family. The tribal village located north of Kajiado in the remote plains was occupied by over fifty Maasai descendants of all ages. It was a culture shock when I learned that each of the members of the village was related; an incestuous family tree that stemmed back over many generations.

The Maasai were fascinating people, who upheld century long customs and cultural practices. With vibrant red as their characteristic tribal colour, they bore Shuka garbs which were cotton wraps attached over one shoulder made with great detail and multiple patterns and colours.

Body modification such as piercings and stretching of the earlobes was present on most elder Maasai, particularly the women. Beadwork is a very common practice as well for décor and for profit. By the end of my journey, I had purchased many handcrafted pieces to adorn my friends and family upon returning home.

The Maasai construct their modular type shelters, or manyattas, from a mixture of cow dung, earth, ash, and local plants and trees. They live a semi-nomadic life and their enclosures and abodes are constructed with the intention that they will not be permanent. The decision to move the village is determined ultimately by the surroundings and the pastoral environment.

With a severe drought in effect for the last three years, the Maasai people – who rely primarily on cattle as their source of livelihood and trade – the detriments of the land were apparent. The cattle were bone thin and while the goats were plentiful, it required several hour treks from the young men and women in the village to gather resources to keep them healthy and productive. The first day of my arrival, it rained for a number of hours. I have to say, I was deemed as a sort of rain god henceforth.

The children welcomed me with open arms, and inquisitive demeanours. When I was not at Eskota primary school at my volunteer teaching role, I spent my time with the younger children embracing their culture, and tribal language – Kimaasai. It became second nature for us to engage in traditional greetings each morning with “Supa” which means “Hello, how are you?”, and the common response being “Ipa”, or “I am fine.”

I became particularly fond of a young female child named Lydia. We would depart early in the morning, hand in hand, to make the long journey to the school together. Although the language barrier and age differentiated us, we shared an unspoken emotional bond that could be mutually understood through as little as a fleeting glance.

She opened my eyes to the unconditional love these children imparted, and humbled me through her zest for life given the limited resources and opportunities she would be afforded. The opportunist attitude was one that I carried forward with me beyond my travels into my everyday life.

Through my time spent with the tribe, I gained invaluable knowledge and understand of their way of life. I learned to appreciate the lax attitude on time, how to barter at the village, and witnessing the impact of Christian missionaries through their lively and moving church services. Watching children no other than 5 years old working feverishly, participating in long-established song and dance events, and living without staples we take for granted like peanut butter became routine for me.

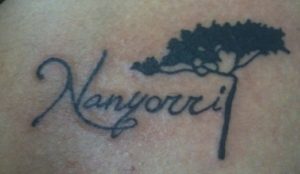

When my time with the tribe came to a close, I was granted intimate time with the matriarch of the tribe, the grandmother. I was graced by her blessings and she gave me a Maasai tribal name, Nanyorri. Nanyorri was selected for me specifically for the relationships that I made over the course of the time in the village and translated to “loved by many.” I have since tattooed my name along with the lone flat-top tree that stood prominently outside the village walls to serve as a reminder of the respect and love I was shown during my time there.